By Environmental Office Manager Angela Chivis and Sr. Environmental Specialist Amy Boetcher

Did you know? According to NASA, the past seven years are the warmest in history, and 2016 and 2020 are the warmest years on record. Furthermore, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources projects temperatures to rise seven to 12 times faster than current temperatures on record, with a 3 to 5-degree Fahrenheit rise in average temperature by 2050. What does this mean for the future of Michigan and the Pine Creek Indian Reservation? By mid-century, Michigan’s climate may feel like Ohio and Kentucky and closer to Missouri and Arkansas by the end of the century.

Changes and increases in temperature cause severe environmental issues for ecosystems and the species inhabiting them, including humans. According to the MDNR, climate change continues to have incredible effects on Michigan’s wildlife, water, land, and air, as well as human physical and mental health.

WILDLIFE

Amongst some wildlife populations, warmer temperatures create more disease and over-population. Some Michigan white-tailed deer populations suffer from Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease and Chronic Wasting Disease. An overpopulation of ticks and midges create more vector-borne disease.

A single bite from an infected midge can transmit EHD and cause fatal hemorrhaging. CWD is contagious through direct contact with an infected animal’s saliva, urine, feces or blood. Once infected, the animal’s brain degenerates, ultimately leading to its death. However, humans are not immune to these changes. As mosquito and tick populations increase, diseases like West Nile virus and Lyme disease also increase.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, natural ecosystem processes such as migration, reproduction, and flower blooming are occurring earlier due to the rising climate. These changes can be devastating to wildlife. Disruptions in migration patterns can lead to food scarcity among animal populations when they arrive before their food source is available.

Some of the most vulnerable species to climate change include the snowshoe hare, lynx, moose, loon, and redback salamander, among others, according to the MDNR. Warmwater fish such as largemouth bass, bluegill, and panfish will thrive with the new climate and experience an increase in habitat. Coldwater species such as walleye and trout will not fare well. Fewer stream miles and lakes will not support these species under the projected future climate.

WATER

Increasing extreme precipitation events are one of the most consistently documented (and predicted) changes in Michigan with a warming climate. Since 1900, precipitation has increased by about 11% in the Great Lakes Region. Water from flash floods does not filter through the soil appropriately, bringing more pollutants, such as pesticides, herbicides and manure, to lakes and rivers. In addition, extreme rain events and snowmelt can cause sewers to overflow into lakes and rivers, threatening recreational uses and drinking water supplies. Flash floods also cause infrastructure damage. Even though we will be getting more extreme precipitation events, we will also see increased evaporation of water, which can reduce water supplies in summer. Increased evaporation also encourages more humidity and is associated with decreased human health. Scientists also agree that we are also likely to see a loss of Michigan wetlands. With more runoff and fewer functioning wetlands, the EPA predicts that climate change will cause additional decreases in Lake Michigan’s water quality.

With increased extreme precipitation and evaporation, climate change’s impact on Great Lakes’ water levels is unclear; however, some things are evident. Already we’ve seen an almost 75% decrease in annual Great Lakes ice coverage between 1973 and 2010. According to the Environmental Law and Policy Center, the Great Lakes seasonal cycles will change. Lakes experience spring and fall turnover each year when water from the top and bottom exchange places. With warming temperatures, this exchange will be farther apart, leading to potentially longer swimming seasons. An extended swimming season also means more time for the algae growing season, potentially leading to more frequent harmful algae blooms.

Each Great Lake experiences different impacts from climate change. A Western Michigan University study suggests that Lake Superior’s temperature is changing most quickly. Our “sixth” Great Lake (groundwater) is estimated to have the same amount of water as Lake Huron. Pumpable groundwater is called an aquifer, which can supply water for irrigation, commercial, industrial and public use – approximately 45% of Michigan residents rely on groundwater for drinking. With more extreme rain events polluting drinking water sources, and other parts of the country short of clean water, our sixth Great Lake is under threat.

Water is connected to our air, wetlands, and the human landscape, such as cities, dams and roads. Human impacts, such as our land use, aquifer mining, and wetland drainage, will leave lasting effects on our waters.

Above: Flash flood from an extreme precipitation event at the Pine Creek Indian Reservation in 2018.

LAND

Particular agriculture and ecosystems will be affected by the changing climate. Crops like soybean and corn will decrease in yield due to hotter summers, while longer frost-free growing seasons could increase wheat yield. National Geographic stated warming climate is causing a reduction in chlorophyll and sugar content in the maple tree sap, requiring more gallons of sap to make one bottle of pure maple syrup. – effectively reducing internal sugar-making processes by nearly 40%.

The National Parks Service projects that cool adapted trees, such as sugar maples, will lose habitat in the U.S., shifting mainly to Canada. This potential shift has harmful implications for Native communities who rely on maple sugar for food and as a spiritual means to connect to the Creator.

Extreme weather and flooding have a heavy impact on Wild Rice crops. Storms knock down growing plants and knock off seeds from the plant before they can be harvested. Heavy rains wash soil and nutrients off the land and into the water, creating algae growth and muddy waters, making Rice hard to grow.

Shown above: Wild Rice is knocked down and uprooted downstream due to high water levels. Historically low water levels on Nottawa Creek off the Pine Creek Indian Reservation expose Wild Rice ordinarily submerged in water, negatively impacting the crop.

AIR

Since 1951, the annual average temperature in Michigan has increased by about 1 degree Fahrenheit. Even one degree of difference can have an impact on how a system functions. With a warming climate, we will continue to experience the effects on the air we breathe. Air is complex because it:

- has myriad components (nitrogen, oxygen, argon, neon), and it carries water, pollen, dust, pollutants, and even living things,

- is interdependent with climate, local weather, solar radiation, urban heat, and natural and human inputs such as wildfires and vehicle exhaust,

- is invisible, and

- doesn’t stay in one place.

Climate scientists study many components of air, including carbon dioxide and methane, two of the most well-known climate change-related components of air. Two components that directly impact human health are ground-level ozone and particulate matter. GLO and PM pollution can cause physical harm to people – causing respiratory issues, increased hospital visits, and premature death.

GLO is different than the ozone layer 10 miles up that protects us from U.V. rays. Power plants, gas engines, and other industrial or commercial processes emit chemicals that react with sunlight to form GLO. Chemical emissions of GLO ingredients can migrate hundreds of miles from where they are created. The American Lung Association’s State of the Air report from 2016 to 2018 suggests that Detroit and Grand Rapids experienced more unhealthy days of high ozone than previously reported. Though the Clean Air Act has and continues to reduce ozone pollution levels, with a warming climate, these levels are predicted to rise and outweigh the reductions we’ve made thus far.

PM is solids and liquids suspended in the air that we can breathe into the lungs. Wildfire smoke is probably the most famous source of PM. However, most PM pollution in the U.S. comes from sources such as power plants and gas engines. Unlike GLO, which requires sunlight for its creation, PM is not dependent on sunlight. PM can even determine how much light penetrates to Earth’s surface. According to the EPA, PM pollution migrates inside homes and buildings.

Wildfires from other states have already impacted Michigan’s air quality. For example, California’s 2018 fires were picked up in Michigan’s breathing envelope, though we didn’t have any newsworthy changes to our sunsets. This year, the Midwest is again getting PM pollution from the Canadian wildfires, and NHBP Tribal Members are helping us quantify it.

Making specific predictions about air quality in the future is difficult, and science does not fully understand climate’s interactions with health yet. However, some projections in climate variations include:

- increased GLO pollution,

- increased frequency and intensity of heatwaves,

- increased wildfires, and

- increased long-range transport of air pollutants and allergens.

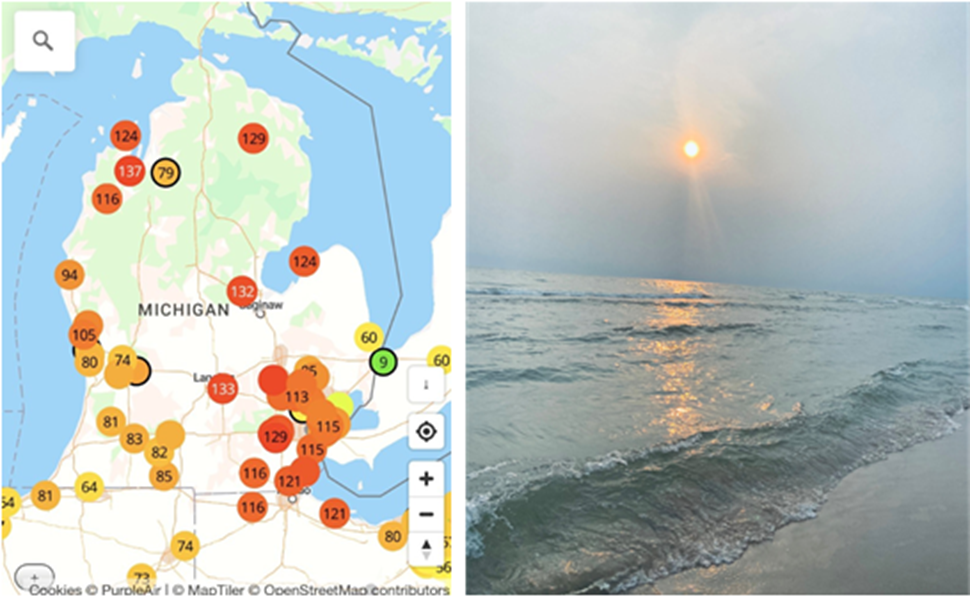

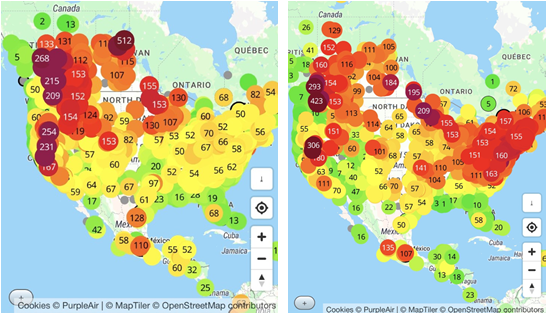

Slide 1 (Left): Map of PurpleAir particulate matter (PM) monitors show unhealthy levels of particulate matter in Michigan after firework displays at 8 a.m. on July 4, 2021. The circle colors represent PM air quality: green (good), yellow (moderate), orange (unhealthy for sensitive groups), red (unhealthy), and maroon (hazardous). Right: Visible haze in Ludington at Lake Michigan, July 31, 2021. Slide 2: Maps of PurpleAir particulate matter monitors show hazardous levels of PM in the Northwest and Canada from wildfires (L) July 15, 2021, and (R) July 20, 2021. Prevailing winds carried newsworthy levels of PM to the Midwest.

MENTAL & PHYSICAL HEALTH

A warming climate also has consequences for mental and physical health. With wildfires, drought, and extreme weather events, climate change can bring stress, depression, and anxiety, which may even be linked to suicide, causing disrupted lifeways and negatively impacting the quality of life.

The U.S. Global Change Research Program reports that a significant portion of people impacted by climate and weather-related natural disasters developed chronic psychological dysfunction and that extreme heat increases physical and mental health problems in people with mental illness, as many psychoactive prescription medications disrupt the body’s ability to regulate temperature.

The scientific journal Nature further demonstrates this by finding that suicide rates rise 0.7% in U.S. counties and 2.1% in Mexican municipalities for a 1 degree Celsius increase in monthly average temperature, suggesting mental well-being deteriorates during warmer climatic periods.

Contaminated waters are becoming a massive problem with temperature increases resulting in bacteria and algae growth. In addition, algal blooms are creating cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins, which can cause illness or death, and flooding is causing sewers to overflow and contaminate water sources. Severe rainstorms can also cause sewers to overflow into lakes and rivers, threatening beach safety and drinking water supplies.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration advised pollen seasons are starting sooner, lasting longer, and producing more pollen than in the past. More frost-free days benefit allergen-producing weeds and elevate the risk of cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses and even death.

FIGHTING BACK

Climate change is affecting the entire web of life on earth. It impacts the air around us, the weather, water, wildlife, and land, interferes with agriculture, increases disease, and risks human physical and mental health.

While we can make a big difference in climate individually, it is important to highlight fossil fuel companies’ impact on climate and the environment. Though a small set of fossil fuel producers can have a significant effect in helping to repair damages, according to a 2017 Carbon Majors Report, these companies distort public access to truths about the harmful effects of fossil fuel use on climate change through advertising and lobbying. We must continue to hold these companies accountable.

There are many moving pieces in understanding climate. The science is constantly changing and often complex. Much lies in our ability to learn about all of the complex moving pieces.

NHBP encourages Tribal Members to fight climate change by recycling, eating more meat-free meals, and planting trees. Other ways to reduce the effects of climate change include using LED lightbulbs to minimize energy usage, driving a fuel-efficient or electric vehicle, regularly tuning up your car and keeping your tires properly inflated, investing in energy-efficient appliances, or riding a train instead of a plane whenever possible.

Works Cited

Barghouthi, Hani. “Wildfires in the West Cause Smoky Skies and Air Pollution in Michigan.” The Detroit News, 20 July 2021, www.detroitnews.com/story/weather/2021/07/20/smoky-skies-midwest-lake-michigan-conditions/8026917002/. Accessed 29 July 2021.

Baron, Jeanne. “Climate Change—Michigan’s State in Year 2100.” Western Michigan University, 30 Jan. 2019, wmich.edu/news/2019/01/51388. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

Blakely, Natasha. “Nestlé Exit: North American Bottled Water Brands Sold to Investment Firm.” Great Lakes Now, 18 Feb. 2021, www.greatlakesnow.org/2021/02/nestle-north-america-bottled-water-brands-sold-investment-firm/. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

BROWN, SARAH. “Global Warming Pushes Maple Trees, Syrup to the Brink.” National Geographic, 2 Dec. 2015, www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/global-warming-pushes-maple-trees-syrup-to-the-brink. Accessed 23 June 2021.

Burke, Marshall, et al. “Higher Temperatures Increase Suicide Rates in the United States and Mexico.” Nature Climate Change, vol. 8, no. 8, 23 July 2018, pp. 723–729, 10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x.

Cameron, L., et al. Michigan Climate and Health Profile Report 2015 Building Resilience against Climate Effects on Michigan’s Health. , 2015.

“Climate Change Effects on Michigan’s Fisheries.” Michigan.gov, Department of Natural Resources, www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,4570,7-350–403361–,00.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

“CWD in Michigan.” Mighigan.gov, Department of Natural Resource, www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,4570,7-350-79136_79608_90516—,00.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

“Dying Birch Trees, Minimal Snowpack, and Ice-Free Lakes Are Just Some…Impacts of Midwest Warming.” National Parks Service, Department of Interior, www.nps.gov/apis/learn/nature/upload/2007%20MWR%20Climate%20Change%20Site%20Bulletin%20-%20Great%20Lakes%20FINAL.pdf.

ELPC. “An Assessment of the Impacts of Climate Change on the Great Lakes by Scientists and Experts from Universities and Institutions in the Great Lakes Region.” Environmental Law & Policy Center, 2019.

“Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) in White-Tailed Deer.” Michigan.gov, Department of Natural Resources, www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,4570,7-350–26647–,00.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

Fann, N, et al. “Ch. 3: Air Quality Impacts.” The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment, vol. Chapter 3, 2016, pp. 69–98, health2016.globalchange.gov/air-quality-impacts.

Fox, Alex. “Earth Could Hit Critical Climate Threshold in next Five Years.” Smithsonian Magazine, 13 July 2020, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/earth-could-hit-key-climate-threshold-next-five-years-180975290/. Accessed 5 Aug. 2021.

Gao, Jinghong, et al. “Impact of Ambient Humidity on Child Health: A Systematic Review.” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 12, 12 Dec. 2014, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4264743/, 10.1371/journal.pone.0112508. Accessed 20 Feb. 2020.

Garris, Heath W., et al. “Forecasting Climate Change Impacts on the Distribution of Wetland Habitat in the Midwestern United States.” Global Change Biology, vol. 21, no. 2, 31 Oct. 2014, pp. 766–776, 10.1111/gcb.12748. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

GLISA. Climate Change in the Great Lakes Region. Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments, 18 June 2014.

Grannemann, N.G., et al. Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4008 Bedrock Aquifers of the Great Lakes Basin. United States Geological Survey, 2000.

Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments Program. “Groundwater Availability | GLISA.” Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments, 2017, glisa.umich.edu/groundwater-availability/. Accessed 29 July 2021.

Griffen, Paul, and et. al. “The Carbon Majors Database CDP Carbon Majors Report 2017 100 Fossil Fuel Producers and Nearly 1 Trillion Tonnes of Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” , 2017.

Gronewold, Andrew, et al. “Fluctuating Great Lakes Water Levels.” University of Michigan, 2015.

Hong, Chaopeng, et al. “Impacts of Climate Change on Future Air Quality and Human Health in China.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 116, no. 35, 12 Aug. 2019, pp. 17193–17200, www.pnas.org/content/116/35/17193, 10.1073/pnas.1812881116. Accessed 1 Apr. 2021.

Hoving, Christopher, et al. “Changing Climate, Changing Wildlife: A Vulnerability Assessment of 400 Species of Greatest Conservation Need and Game Species in Michigan.” Michigan State Unviersity, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Apr. 2013, www.canr.msu.edu/uploads/234/62936/CLIMATE_CHANGE.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

Keenan, Trevor F., et al. “Increase in Forest Water-Use Efficiency as Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Concentrations Rise.” Nature, vol. 499, no. 7458, 18 July 2013, pp. 324–327, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23842499/, 10.1038/nature12291. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

MDEQ. Fact Sheet GROUNDWATER STATISTICS. , 2018.

“Michigan Emerging and Zoonotic Disease.” Michigan.gov, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, July 2020, www.michigan.gov/documents/emergingdiseases/Final_2019_Annual_Summary_695711_7.pdf. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

Michon, Scott. “Climate & Allergies | NOAA Climate.gov.” Www.climate.gov, NOAA, 6 July 2018, www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-and/climate-allergies. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

Miller, Nathaniel. “Testimony of Nathaniel Miller on Michigan’s Senate Bill 1211.” Audubon Great Lakes, 17 Dec. 2018, gl.audubon.org/news/testimony-nathaniel-miller-michigans-senate-bill-1211. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

Morrison, Angelica A. “Climate Change Threatens Maple Trees — and Syrup.” News.wbfo.org, Toronto Public Media, 3 2018, news.wbfo.org/post/climate-change-threatens-maple-trees-and-syrup. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

NASA. “NASA Climate Kids :: What Is ‘Global Climate Change’?” Nasa.gov, 2018, climatekids.nasa.gov/climate-change-meaning/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

NASA Global Climate Change. “10 Interesting Things about Air – Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet.” Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2 Nov. 2016, climate.nasa.gov/news/2491/10-interesting-things-about-air/. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

National Geographic Society. “Freshwater Resources.” National Geographic Society, 28 June 2019, www.nationalgeographic.org/article/freshwater-resources/.

Nolte, C.G., et al. “Air Quality. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II.” Https://Nca2018.Globalchange.gov/Chapter/13/, US Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, 2018. pp. 512–538. doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH13.

Patz, Jonathan A., et al. “Climate Change and Waterborne Disease Risk in the Great Lakes Region of the U.S.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 35, no. 5, 1 Nov. 2008, pp. 451–458, www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(08)00702-2/fulltext, 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.026.

Peach, Sara. “Why Climate Change Is like a Fever» Yale Climate Connections.” Yale Climate Connections, 30 Aug. 2017, yaleclimateconnections.org/2017/08/why-climate-change-is-like-a-fever/. Accessed 28 July 2021.

“Report: Fossil Fuel Industries – the Goliath of Climate-Related Lobbying Efforts, Spent Billions.” DrexelNow, 19 July 2018, drexel.edu/now/archive/2018/July/Report-Fossil-Fuel-Industries-Spent-Billions-on-Climate-Lobby/. Accessed 9 Aug. 2021.

Seedang, Saichon. “Water Withdrawals and Water Use in Michigan (WQ62).” MSU Extension, 20 Oct. 2015, www.canr.msu.edu/resources/water_withdrawals_and_water_use_in_michigan_wq62. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

Sierszen, Michael E., et al. “A Review of Selected Ecosystem Services Provided by Coastal Wetlands of the Laurentian Great Lakes.” Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, vol. 15, no. 1, 1 Jan. 2012, pp. 92–106, read.dukeupress.edu/aehm/article-abstract/15/1/92/168746/A-review-of-selected-ecosystem-services-provided, 10.1080/14634988.2011.624970. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

State of Michigan. STATE of MICHIGAN 99TH LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION of 2018. Senate Bill No. 1211. , 28 Dec. 2018.

Sykes, Jon, et al. Groundwater Science Relevant to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement: A Status Report. Great Lakes Executive Annex 8 Subcommittee, Oct. 2015.

United Nations. “Scarcity | UN-Water.” UN-Water, 2021, www.unwater.org/water-facts/scarcity/.

University, Stanford. “The Effects of Climate Change on Suicide Rates | Stanford News.” Stanford News, Stanford University, 29 Mar. 2019, news.stanford.edu/2019/03/29/effects-climate-change-suicide-rates/.

US EPA. “Health and Environmental Effects of Particulate Matter (PM) | US EPA.” US EPA, 9 May 2019, www.epa.gov/pm-pollution/health-and-environmental-effects-particulate-matter-pm.

—. “Indoor Particulate Matter.” US EPA, 15 Aug. 2014, www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/indoor-particulate-matter.

—. “What Climate Change Means for Michigan.” EPA.gov, United Stated Environmental Protection Agency, Aug. 2016, 19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-09/documents/climate-change-mi.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2021.

—. “What Is Particle Pollution?” US EPA, US Environmental Protection Agency, 12 Sept. 2014, www.epa.gov/pmcourse/what-particle-pollution.

VÖRÖSMARTY, C.J., and D. SAHAGIAN. “Anthropogenic Disturbance of the Terrestrial Water Cycle.” BioScience, vol. 50, no. 9, 2000, p. 753, 10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0753:adottw]2.0.co;2.

Wang, Jia, et al. “Temporal and Spatial Variability of Great Lakes Ice Cover, 1973–2010*.” Journal of Climate, vol. 25, no. 4, 8 Feb. 2012, pp. 1318–1329, digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1513&context=usdeptcommercepub, 10.1175/2011jcli4066.1. Accessed 4 Aug. 2021.

Weir, Kirsten. “Climate Change Is Threatening Mental Health.” Https://Www.apa.org, Aug. 2016, www.apa.org/monitor/2016/07-08/climate-change. Accessed 28 Apr. 2021.

0 Comments