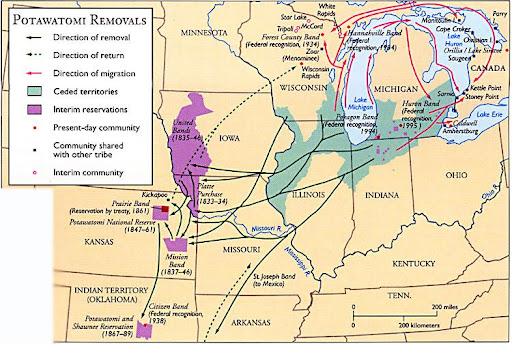

Figure 27. Map Demonstrating the Potawatomi Routes of Forced Removal, Migration to Avoid Removal, and Return from Removal. Reprinted from “Potawatomi Removals,” by Kalamazoo Public Library Staff (Ed.), 2020 (https://www.kpl.gov/local-history/kalamazoo-history/native-americans/match-e-be-nash-she-wish/).

While many of the Potawatomi of northern Indiana were removed as part of the heartbreaking 1838 Trail of Death, the non-Pokagon Potawatomi of Southwest Michigan were given a two-year pardon due to Federal financial problems related to the economic depression of 1837 and were not removed until the summer of 1840 (Leatherbury, 1977, p. 67; Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10 Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 277).

By this time, their traditional means of providing for their families had suffered greatly, and the Nottawaseppi Huron Band was in a dramatically weakened state. To make matters worse, the Tribe suffered greatly during the winter of 1839-1840 because the government intentionally limited assistance and provisions to make removal to Kansas more achievable (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10).

Gathering the NHBP Tribal members living on the Nottawaseppi Reservation for removal was not an easy task. Even in their weakened condition, the members’ reluctance to relocate made enforcing this removal challenging for the U.S. Government. To accomplish this daunting task, in the late summer of 1840, the government dispatched General Hugh Brady and nearly “200 regulars and 100 horsemen” to search the forests and prairies from Detroit to Marshall (Leatherbury, 1977, p. 80; Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10).

The distressed Tribal members eventually abandoned the Nottawaseppi Reservation as word of their imminent capture spread (Leatherbury, 1977, p. 80; Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10). Many migrated north of the Grand River to reside with Ottawa/Odawa kin either in Mission Communities or in Ottawa Villages in the lands recently ceded by the Ottawas/Chippewa to the United States in the 1836 Treaty of Washington. Many fled to Canada (where several were captured along the way), while others withdrew “deep into the woods and thickets where they hid” unnoticed (Leatherbury, 1977, p. 84; Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10).

For two months, Brady’s troops and volunteers searched for the Huron Potawatomi that were in hiding. To finally flush them out of hiding, General Brady “offered rewards and other incentives” for their capture, with “special rewards” being offered for the apprehension of “Tribal leaders, including the half-brothers Pamptopee and Chief John Moguago” (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10). By September 19, 1840, 439 members of the Huron Potawatomi were captured and kept as prisoners in a temporary camp near Marshall (Clifton et al., 1986, p. 71; Leatherbury, 1977, p. 88; Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 12). On October 15th, 1840, they began their forced trek to a reservation in Kansas (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 12).

Much of what was learned of the journey came from a journal (now in the Kingman Museum, Battle Creek, Michigan) left by Lucius Buell Holcomb, a white merchant from Athens. Holcomb was married to an NHBP Tribal member and spoke fluent Potawatomi. He demonstrated his loyalty and friendship to the Tribe on numerous occasions as he supported their causes and accompanied them on their removal trek. His journal described that Chief John Moguago and a few other NHBP members escaped from their armed guards while their escorts explored at Skunk Grove, Illinois (near Chicago). They returned to the Athens, Michigan area, where other members of the tribe, including future Chief Pamptopee, had avoided capture (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 12).

The remaining exiles continued west, mostly on foot but a few on horseback, until they arrived at the Illinois River near Peru, Illinois. At this point, they were forced onto steamboats, where soldiers took their horses and most of their possessions, not compensating them for their personal property. The trek continued southwest via the Illinois River to its opening at the Mississippi River until they entered the entrance of the Missouri River near Alton. The journey became arduous at this juncture. The boats headed upriver, and delays were frequent as they encountered shoals and sand bars. Food and fresh water were scarce; sanitation was disgraceful; medical care was non-existent; winter was ominous (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 12).

Regardless of the wearying state of the NHBP people, the boats pressed on towards Kansas. When they finally came ashore, the Tribal Members were forced to walk 100 miles to the designated Indian Territory near the Osage River (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 12).

The suffering endured by the NHBP people during the 750-mile, nearly 40-day journey to Kansas was unthinkable; a number of NHBP people were known to have perished along the route.

Recalling the band’s removal in 1840, young John Moguago commented: “…when the whites and their Soldiers came we had to Relinquish our claims with out [sic] councel [sic] or plea to It…we shed not a tear on the…graves of our childr [sic] and parents but left them and Removed off” (Leatherbury, p. 108).

References:

Kalamazoo Public Library Staff (Ed.). (2020). Potawatomi Removals [Map]. https://www.kpl.gov/local-history/kalamazoo-history/native-americans/match-e-be-nash-she-wish/

Leatherbury, J. (1977). A History of Events Culminating in the Removal of the Nottawa-Sippe Band of Potawatomi Indians.

Rodwan, J., & Anewishki, V. (2009). Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress. Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi Environmental Department.

Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc. (1995). United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs Branch of Acknowledgement and Research. https://www.bia.gov/sites/bia.gov/files/assets/as-ia/ofa/petition/009_hurpot_MI/009_pf.pdf

The Hugh Brady Letters and the Removal of the Potawatomis. (2014). http://www.michiganinletters.org/2014/08/the-hugh-brady-letters-and-removal-of.html