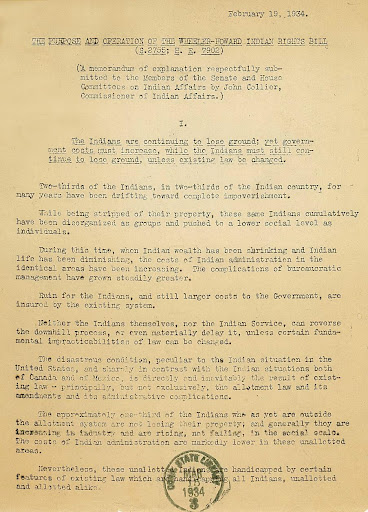

Figure 50. A Page from John Collier’s Memorandum to the Members of the Senate and House Committees on Indian Affairs. Reprinted from “The Purpose and Operation of the Wheeler-Howard Indian Rights Bill (S. 2755; H.R. 7902),” by J. Collier, 1934, p. 1 (https://cslib.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4005coll11/id/513/).

Two-thirds of the Indians, in two-thirds of the Indian country, for many years have been drifting toward complete impoverishment. While being stripped of their property, these same Indians cumulatively have been disorganized as groups and pushed to a lower social level as individuals. During this time, when Indian wealth has been shrinking and Indian life has been diminishing, the costs of Indian administration in the identical areas have been increasing. The complications of bureaucratic management have grown steadily greater. Ruin for the Indians, and still larger costs to the Government, are insured by the existing system. Neither the Indians themselves, nor the Indian Service, can reverse the downhill process, or even materially delay it, unless certain fundamental impracticabilities of law can be changed (Collier, 1934, p. 1).

The Indian Reorganization Act (“IRA,” “Wheeler-Howard Act”), signed June 18th, 1934, was intended to encourage tribes to assume more control of their governance and help change the aforementioned “fundamental impracticabilities of law,” which was resulting in so many problems in Indian Country.

The press signaled this act as an “Indian New Deal” program; it provided tribal participants assurances that their land would be held forever in Federal trust and that eligible tribes could develop their economies. Albert Mackety, Levi Pamp, and another NHBP member, Austin Mandoka, who was Chairman of the Athens Indian Committee, learned of the IRA and believed the legislation could benefit the community (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 55).

These leaders collected 62 signatures from the adults of the NHBP. The list of signatures was attached to Austin Mandoka’s letter, dated March 20th, 1934, asking John Collier, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to clarify the group’s eligibility status relative to the IRA legislation. The letter pleaded their case:

The Indian children have been attending Mt. Pleasant Indian School in the past years, but due to the Government’s economic program, were forced out, making it doubly hard for the parents to obtain more food and clothing at home. We as a body are praying for aid, in the form of more land, and farm implements for the purpose of making our living. Will you kindly send us a reply, regarding our status in the Indian Bill S.2755 (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 55).

In correspondence, dated April 21st, 1934, addressed to Austin Mandoka, Commissioner Collier confirmed that the Athens Indian Reservation was eligible under the IRA; however, the NHBP’s ability to actually realize the promise of the IRA was eventually thwarted due to budgetary limits resulting from the Great Depression.

In 1939, responding to multiple requests from the Pine Creek settlement and Indian tribes all over Michigan, the BIA commissioned John H. Holst to study the economic and assimilation status of Indian communities in southern Michigan. Within this study, entitled “A Survey of Indian Groups in the State of Michigan 1939,” Holst reported,

The Athens group is small. The State holds a sort of trust over 120 acres of land on which the so-called Athens group reside. The land is divided into six 20-acre units. About a third of it is cultivated. They make some baskets but depend mainly upon outside employment (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, pp. 347-348).

This report concluded that local and state agencies were fully capable of providing services to the small “remnant” bands of Indians in southern Michigan. The study also determined that, with the closure of the Mt. Pleasant Indian Boarding School, the U.S. Department of the Interior could move the last Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) monies from Lower Michigan to other U. S. locations where tribes resided (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 56).

Based on Holst’s 1939 survey, Walter V. Woehlke, of the Department of the Interior prepared a memorandum to COIA John Collier recommending withdrawal of activities from Lower Michigan. Woehlke summarized the Government’s position as follows:

Unless we have the funds and personnel to do a real job in Lower Michigan, we should stay out of that territory. We all know that neither the personnel nor the funds are available. Hence, it would be a crime to disturb the present excellent relations between the State, Counties, and Indians. I doubt whether it is possible to obtain from Congress special legislation and special appropriations for the benefit of the Lower Michigan Indians; even if it were possible to obtain such aid, I doubt the wisdom of establishing such a precedent (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 56).

On May 29, 1940, in explicit consideration of Holst’s report and Woehlke’s memorandum, COIA Collier issued a policy limiting the further extension of Federal services to Indians in Lower Michigan. That same year, the Pine Creek community finally received a reply to their letter written to John Collier in 1934, requesting his assistance in making the NHBP an eligible IRA Indian Group. The reply stated:

…that there be no further extension of Organization under the Indian Reorganization Act in Lower Michigan. That the Indian Office shall not attempt to set up any additional or supplementary educational or welfare agencies for the Indians of Lower Michigan that in any way tends to recognize Indians as a separate group of citizens (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 55).

The NHBP’s hope of federal services and aid through Collier’s assistance ended with this letter. Given Collier’s decision, emphasized by Woehlke, Pine Creek leaders had to look elsewhere for services to support their subsistence economy (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 56).

References:

Collier, J. (1934). The Purpose and Operation of the Wheeler-Howard Indian Rights Bill, (S. 2755; H.R. 7902). (25322491). United States. Office of Indian Affairs.; Connecticut State Library. https://cslib.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4005coll11/id/513/

Rodwan, J., & Anewishki, V. (2009). Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress. Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi Environmental Department.

Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc. (1995). United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs Branch of Acknowledgement and Research. https://www.bia.gov/sites/bia.gov/files/assets/as-ia/ofa/petition/009_hurpot_MI/009_pf.pdf