He is troweling through, centimeter by centimeter, searching, looking, examining the ground for any artifact that may reveal historical context about those who came before us—hour after hour, day by day.

This is the daily life for Citizen Potawatomi Nation Tribal Member Cole Rattan, 28, a soon-to-be “shovel bum” or field tech, working toward his bachelor’s degree in Cultural Resource Management within Native American Studies at East Central University in Ada, Oklahoma.

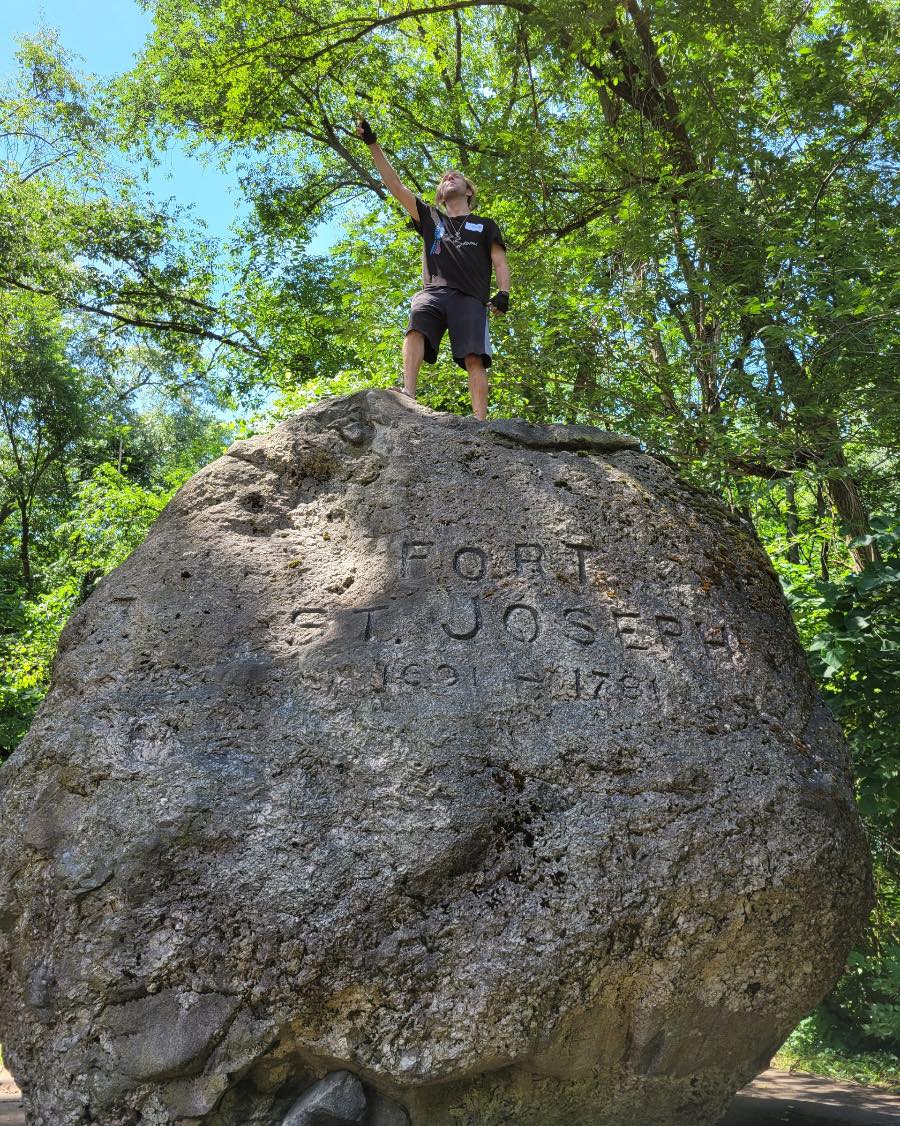

“When I was researching online where to perform field work, such as archaeological digs throughout the country, once I read, ‘Fort St. Joseph,’” Rattan said. “I was immediately drawn to this location because my Tribe was once known as the ‘St. Joseph Band of the Potawatomi,’ and this is where we were from.”

One of the oldest field schools in the state, located in Niles, Michigan, according to its website, the Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project “is an ongoing joint initiative of the City of Niles and Western Michigan University to excavate, interpret and preserve the material remains of Fort St. Joseph, a mission, garrison and trading post occupied from 1691 to 1781 by the French, then the British.”

“We know that there were 14 families who lived in this fort,” Rattan said. “But we don’t know exactly the size of this fort, as the wall posts, or palisades, haven’t been found yet.”

Rattan resides in Tecumseh, Oklahoma, and is one of 37,000 enrolled Tribal Members of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

Rattan has been conducting research on his family for about a year now and is still pursuing leads.

Rattan traces his family back to Potawatomi Chief Naunongee, a Headman in the Calumet region and prominent Gigo Clan Member who fought and died at the Battle of Fort Dearborn. His daughter Chopa Neeboash married a man named Francois Pierre Chevalier, who also came to be a Headman for the Potawatomi, known as Chief Shobbonier. It’s possible that he was Métis or of mixed Indigenous descent. Francois belongs to the same Chevalier family that was at Fort St. Joseph, but his place in the family tree hasn’t been nailed down yet, as more research and primary sources are needed to find his parents and lineage.

“We were removed and displaced from our Ancestral homeland and sent to Oklahoma, where the soil isn’t as good. It’s difficult to grow things here, and we can’t tap trees for maple syrup because it doesn’t stay consistently cold long enough. If you don’t like the weather in Oklahoma, wait five minutes.”

Rattan’s research interests are the Algonquian-speaking Peoples, anything related to the Council of Three Fires Neshnabék —Bodéwadmi, Ojibwe, and Odawa —and the Fur Trade.

Rattan must perform six credit hours of field school before he can work on any archaeology or cultural resource management jobs.

“If you want to work as an archaeologist in America, as exotic as going to Egypt or Japan may sound, there are different excavation methods, as well as rules and laws for archaeology in the States. So, the field school needs to be in the U.S. For my first field school, I worked under Dr. Holly Jones at a Pre-Caddoan site last year that is possibly 3,000 years old.”

Rattan is a guest student of Western Michigan University for the summer, enrolled in the St. Joseph Archaeology Field School course, which costs thousands of dollars. The former Marine, who is saving his GI Bill for his approaching graduate school, doesn’t have funds to cover the field school costs, as his loans and Tribal scholarship were already used for his spring and summer classes at East Central University in Oklahoma.

Before Rattan finalized his plans to come to Western, the Language Director at the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Justin Neely asked for help on social media, and NHBP Tribal Member and Food Sovereignty Director Nickole Keith welcomed Rattan as her house guest for the eight-week program.

“I budgeted enough for gas and food for my stay in West Michigan, but Nickole letting me stay in her home really saved my hide! Nickole and her family have been more than welcoming to this Southern boy,” Rattan said. “Everyone on The Rez has treated me great, and I have really enjoyed my time with them. It feels like family.”

Each weekday he drives from Keith’s home to Western’s Main Campus at 7:45 a.m., where he and seven other students either work in the lab or are shuttled to the site in Niles, arriving by 9:15 a.m. to work in partners. Each pair is assigned a plot – or “unit” – of land that measures 1 by 2 meters. The pairs skim through their unit with trowels, centimeter by centimeter, examining the ground and sorting whatever treasures the dirt may surrender. At 3 p.m., the students head back to campus.

“This site is guarded in multiple ways. It is protected by the St. Joseph River on one side, and we would not be able to dig where we are digging without the dewatering machine,” Rattan said. “It is protected by a landfill on the other, making it dangerous to dig in certain areas because of the industrial trash, sharp metal and glass. Finally, if there are people digging of their own accord or doing something shady, the community does a good job of calling it in. There’s also a police officer who patrols the area.

“My partner and I have found a diverse number of artifacts,” Rattan said. “Bone fragments, teeth, window and container glass, hand-wrought iron nails, red ware, faience, pottery, a tinkling cone, mulberry and seed beads, lead shot, a gunflint, and clay pipe stems. We have left both the Alluvium (Level 1) and Plow Zone (Level 2) and have started making our way into the Occupation Zone (Level 3). We are currently 40 centimeters below datum in the unit and have been finding artifacts lying horizontally in their original position.

“Archaeology is a destructive science,” Rattan said of the process that requires excavation or removal of the ground and its materials, never to be the same again. “That is why you have to be precise, meticulous. You have to indicate not only what you have found, but where and how you found it, so you can study and understand the provenience. Picking up artifacts and removing them ruins the provenience the artifacts had to the rest of the site. If you want to be a friend to the archaeological record, write it down, take a picture, call an archaeologist, and most importantly, leave it where you found it.”

When the teams aren’t in the field, they clean and curate their findings in the lab. At the end of the semester, in mid-August, the students will fill their units back in with the same dirt they removed, marked with outlines that the team was there.

“The Citizen Potawatomi Nation has always helped out me and my family,” Rattan said. “I would like to become qualified enough to come back and work for them someday to give back for all they’ve done for me. If that doesn’t happen, I would like to work for a Tribe in the Great Lakes Region. There need to be more Indigenous archaeologists so we can be in charge of how our story gets told in a respectful way, while at the same time being directly involved with the archaeology and repatriation of our own cultural artifacts.

“I have a lot of people rooting for me back home and here in West Michigan, and that means a lot to me: My Grandpa Donald Moutaw, who helped me get up here, and Mike and Debbie Riddle (CPN) back home and Aunty Gwynn and Muskrat (NHBP) for helping me get the Potawatomi Gathering. Igwiyen!”

This fall semester, Rattan will continue giving back by serving as an intern at the award-winning Citizen Band Potawatomi Nation Cultural Center in Shawnee, Oklahoma.

The WMU students document their finds daily on social media and their blog sites, and the Facebook page can be found here.

0 Comments