Timeline Demo 3

Historical Events Timeline

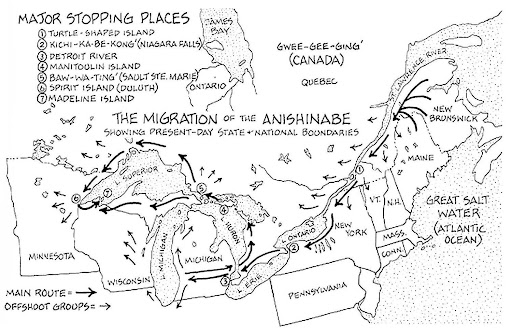

Figure 1. The Migration of the Anishinabe Showing Present-Day State and National Boundaries. Reprinted from”The Migration of the Anishinabe” by E. Benai, 2010, The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway, p. 102. The”Council of Three Fire” (in Anishinaabe: Niswi-mishkodewinan), is known as many entities: the”People of the Three Fires” the”Three Fires Confederacy” or the”United Nations of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Indians” The Council is an enduring Anishinaabe alliance of the Chippewa (a.k.a., Ojibwa or Ojibwe), Ottawa (a.k.a., Odawa or Odaawaa), and Potawatomi (a.k.a., Pottawatomie) North American Native tribes. Originally one people or a collection of closely related bands, the…

Read More

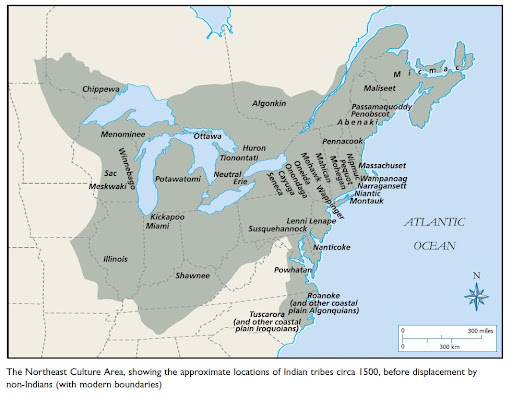

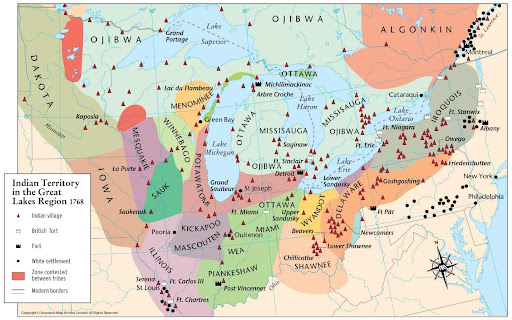

Figure 3. The Northeast Culture Area, showing the approximate locations of Indian tribes circa 1500, before displacement by non-Indians (with modern boundaries). Reprinted from “Northeast Woodlands Culture,” n.d., Retrieved from www.ya-native.com/Culture_NortheastWoodlands/index.html. In the early 1500s, the Council of Three Fires split off into three separate groups: Chippewa (“Keepers of the Faith”) Ottawa (“Keepers of the Trade)” Potawatomi (“Keepers of the Sacred Fire”) The Potawatomi migrated south to Michigan’s Lower Peninsula and lived there until the 1640s and 1650s (Potawatomi History | Milwaukee Public Museum, n.d.). Around 1665, the League of the Iroquois, from upstate New York, drove the Potawatomi to…

Read More

Figure 4. Jean Nicolet’s presumed route through the Great Lakes. Adapted from “Jean Nicolet’s Search for the South Sea,” by N. Risjord, n.d., p. 8, Retrieved from https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/11381679/jean-nicolets-search-for-the-south-sea-wisconsin-historical-society. In 1634, while searching for the famed Northwest Passage, the French explorer Jean Nicolet (ca. 1598 – 1642) arrived at what would become Green Bay, Wisconsin (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020). Upon arrival, Nicolet encountered a small group of Potawatomi; however, most of the Potawatomi lived in Michigan at this point in time. Therefore, this group that met Nicolet was most likely only visiting the region (Milwaukee Public Museum, n.d.). References:…

Read More

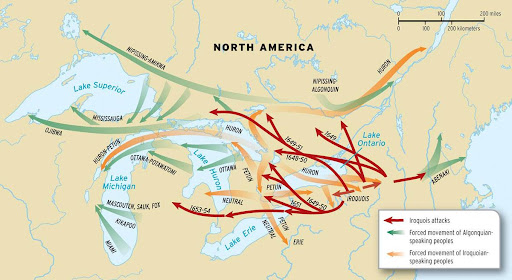

During the mid-seventeenth century, in an attempt to dominate the fur trade as well as the trade between European markets and tribes of the western Great Lakes region, the Iroquois, supplied with Dutch and English firearms, aggressively expanded their territory westward (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 1). The French, economically dependent on the fur trade, aligned with the Algonquian-speaking tribes in the area to defend their hold on the precious commodity. This aggression resulted in several conflicts between the Iroquois Confederation, primarily Mohawk (one of the five core tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy), and most of the Algonquian-speaking tribes of the Great Lakes…

Read More

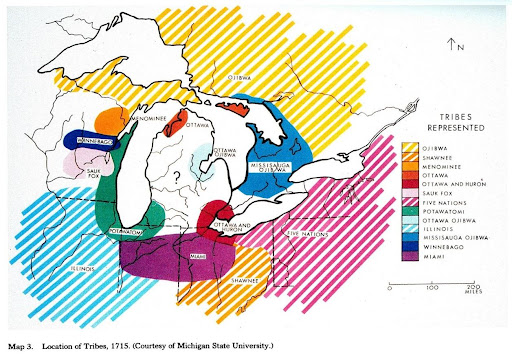

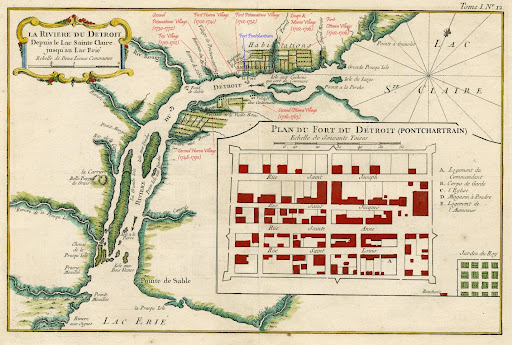

The French and Algonquin* started pushing the Iroquois back to New York in 1687 (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 1). As the invaders withdrew, the Potawatomi journeyed south along Lake Michigan, reaching the southern shores around 1695 (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 1). One band established a home near a Jesuit mission along the St. Joseph River in southwestern Michigan (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 1). Many other Potawatomi soon settled near the newly built Fort Pontchartrain in Detroit in 1701 (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 1). By 1716, the Potawatomi would set up many villages from Detroit to Milwaukee (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 1). * The Algonquin people…

Read More

In the 1700s, three groups of Potawatomi were identified based primarily on their locations (Sultzman, 1998, p. 3): The “Detroit Potawatomi” of southeast Michigan The “Prairie Potawatomi” of northern Illinois The “Saint Joseph Potawatomi” of southwest Michigan The Beaver Wars officially ended on August 4th, 1701, with the signing of a treaty known as the “Great Peace of Montreal.” The governor of New France was present, as were 1,300 representatives from 39 Native American Tribes, including the Iroquois, who also relinquished their previously conquered territory (Francis et al., 2006). Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac landed on July 24th, 1701, and began preparing to construct Fort…

Read More

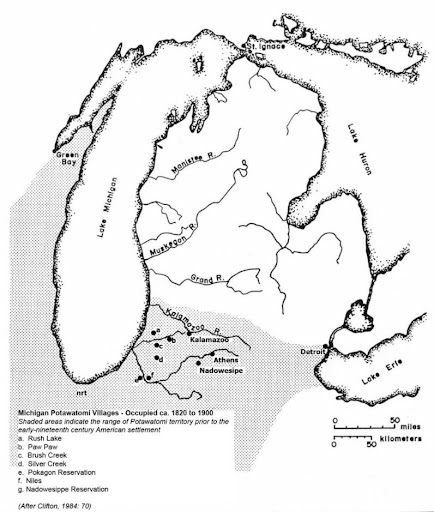

The Detroit Potawatomi left their villages on the Detroit River in October 1763 and spread their villages to the south and west, setting up various hunting camps. In 1765, they established several villages on the Huron River and, at that time, became known as “Potawatomi of the Huron” (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 39) The departure of the Potawatomi from Detroit can be confirmed: in a deed dated May 26th, 1771, ratified July 15, 1772, in which the tribal chiefs of the nation of Potawatomi at Detroit granted to Robert Navarre…

Read More

Signed August 3rd, 1795, the Treaty of Greenville followed negotiations after the Native American loss at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. This defeat ended the ten-year-long Northwest Indian War and established the Greenville Treaty Line, which for many years became a boundary between territory that was acknowledged as remaining under the sovereign authority of various Native American tribes and had been ceded by tribes to the United States government that was open to European-American settlers. The Native American tribes involved in this treaty ceded a significant area of modern-day Ohio, the future site of downtown Chicago, the Fort…

Read More

Figure 17. Michigan Treaties. Reprinted from “People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan,” by J. Clifton, G. Cornell, and J. McClurken, 1986, p. 36. Following its independence from Britain, the rapidly increasing population of the United States demanded access to new lands for settlement. To meet these demands, the United States Government negotiated numerous treaties by which Indian tribes would “cede” or sell large portions of their territory to the United States while “reserving” (withholding from sale) certain areas (referred to as “reservations”). Tribes, including the Huron Potawatomi, would usually also “reserve” rights to continue…

Read More

Figure 21. Michigan Treaties. Reprinted from “People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan,” by J. Clifton, G. Cornell, and J. McClurken, 1986, p. 36. The Potawatomi signed the first Treaty of Chicago on August 29th, 1821, ceding much of their remaining land to the U.S. Federal Government (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 6). Similar to the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, this treaty impacted the band of Huron Potawatomi. Most settled on a four-mile square tract of land reserved under this 1821 treaty that was known as the “Nottawaseppi Reservation [located] on the banks of the…

Read More

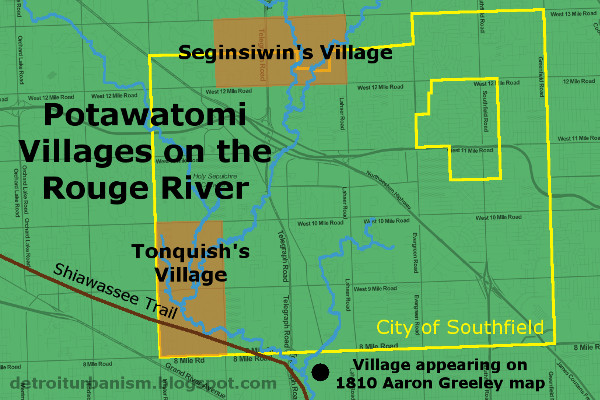

Figure 23. Potawatomi Villages on the River Rouge Ceded in the 1827 Treaty of St. Joseph. Reprinted from “Detroit Urbanism: Indian Villages, Reservations, and Removal,” by P. Sewick, 2016 (http://detroiturbanism.blogspot.com/2016/03/indian-villages-reservations-and-removal.html). As part of the Treaty of St. Joseph, signed September 19th, 1827, the Potawatomi ceded to the U.S. Government settlements along the River Rouge and River Raisin in southeast Michigan and areas in southwest Michigan around the Kalamazoo River (Printed Copy of the Ratified Treaty Between the United States and the Potawatomi Indians Signed at St. Joseph, Michigan Territory, on September 19, 1827, 1829). The second paragraph in this new…

Read More

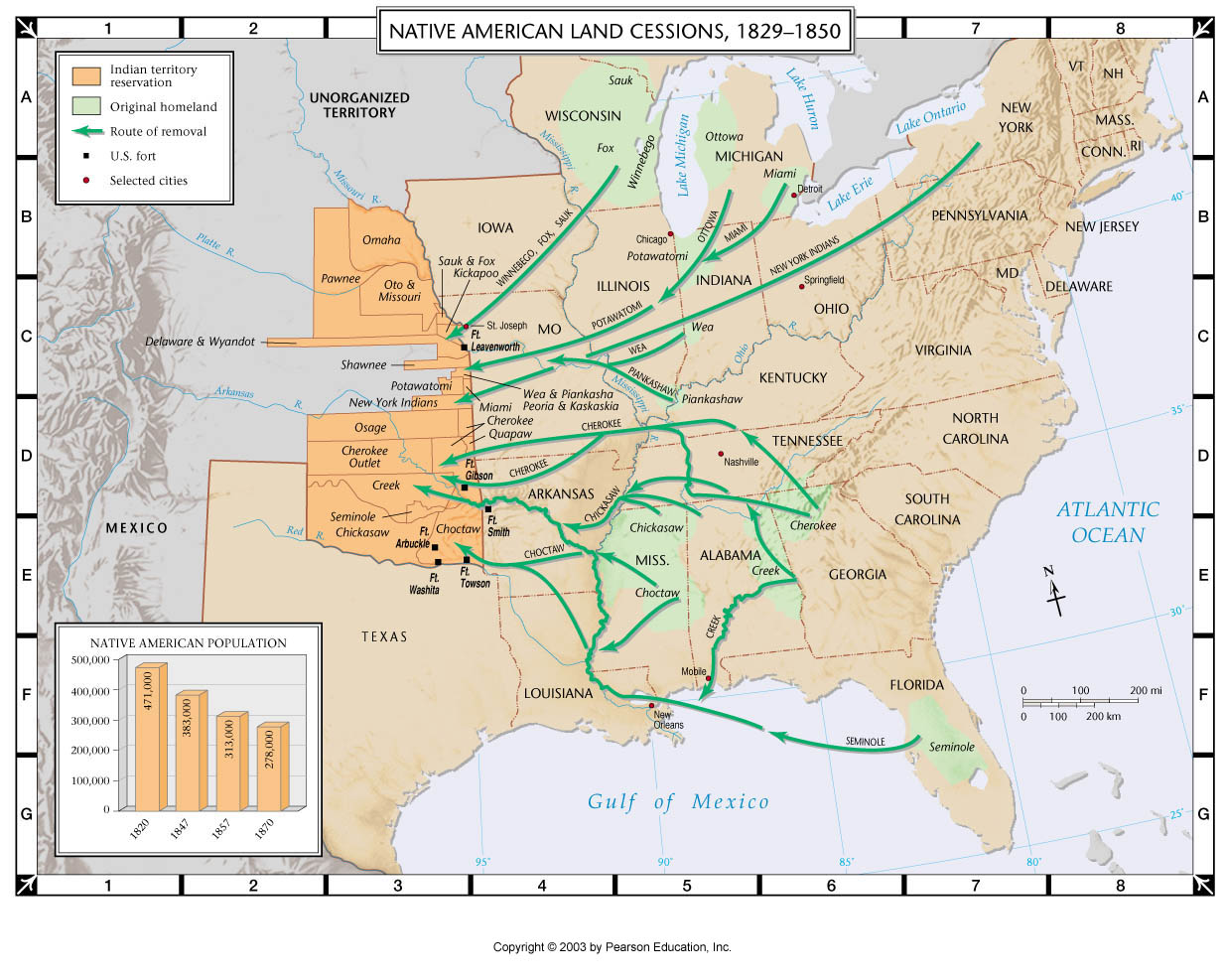

Figure 24. Results of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Reprinted from “Native American Land Cessions, 1829-1850,” by Pearson Education, 2003 (https://wps.pearsoncustom.com/wps/media/objects/5407/5537171/atlas/Resources/ah3_m002.jpg). While the Huron Potawatomi, and other Potawatomi, generally maintained peaceful relations with their new non-Indian neighbors, the increased pressure from settlers, many of whom illegally entered Indian lands, often resulted in violent conflict between settlers and the resident Indian tribes. The solution championed by Andrew Jackson and others in the U.S. Government became the nineteenth-century policy referred to as “Indian Removal,” by which Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River would be encouraged to sign treaties giving up the…

Read More

Unfortunately, the Nottawaseppi Reservation was a momentary home in Michigan. In the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, signed September 26, 1833, the Potawatomi (including the Nottawaseppi Huron Band) ceded the Nottawaseppi Reservation and other lands located in Michigan to the United States. The treaty required the Potawatomi to remove west to new reservations in the Kansas Territory. Consequently, the U.S. Government ordered an involuntary removal of nearly every band of Potawatomi to Kansas by 1838. Between 1833 and 1840, the ancestors of today’s Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (NHBP) continued to reside on the ceded Nottawaseppi Reserve and other lands…

Read More

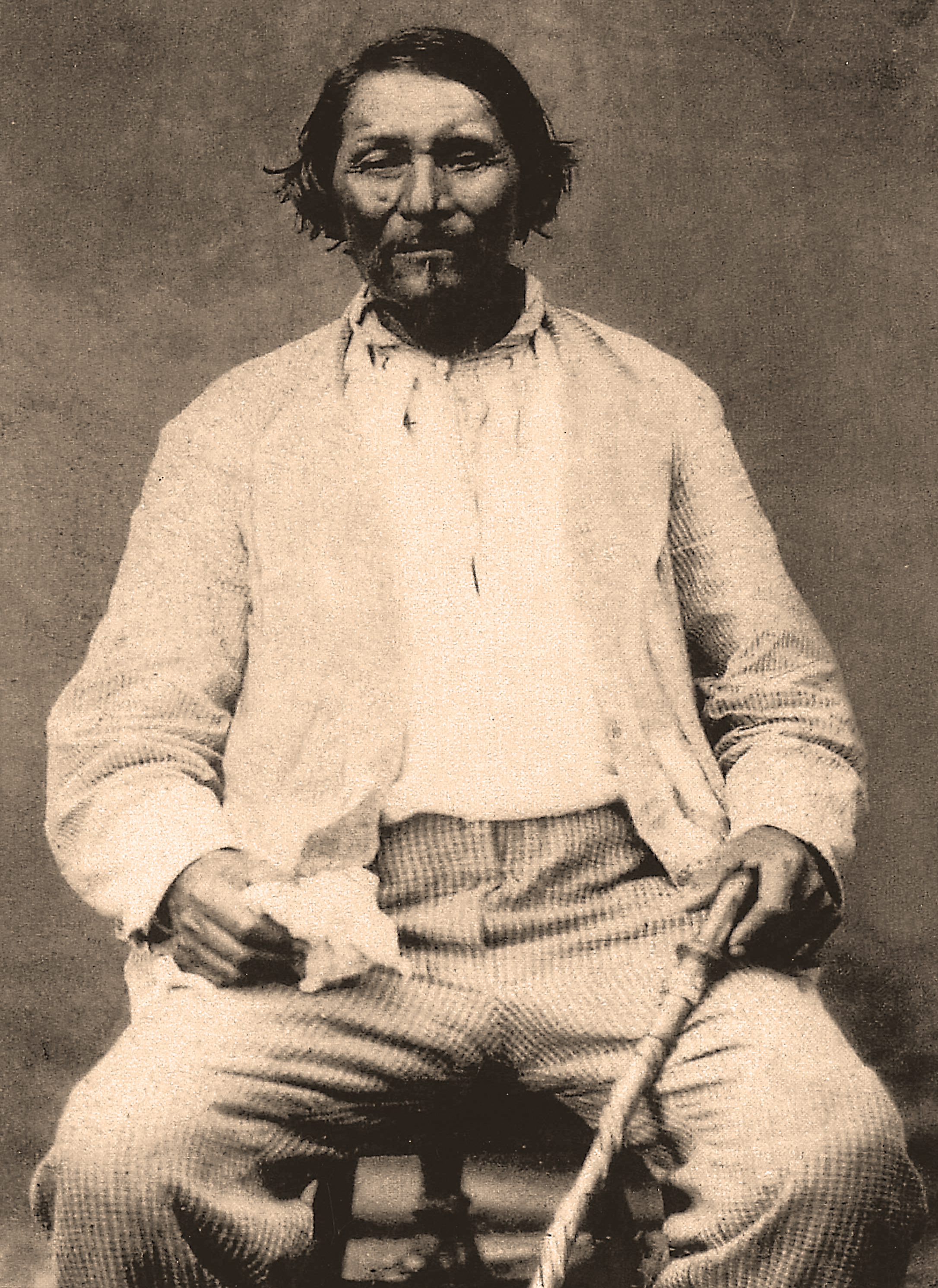

Figure 26. Photograph of Chief Moguago. Reprinted from “Chief John Moguago,” ca. 1860. “Young John” Moguago, son of “Old” Moguago and grandson of Mogoagon, emerged as the head chief of the band upon the death of Sau-au-quett (Leatherbury, 1977, p. 100; Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10). His birth date is unknown, but it was thought to be close to 1795 (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10). Moguago was given the Christian name of “John,” also at an unknown point in time (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10). Moguago had no children and served as chief from about 1839 to 1863…

Read More

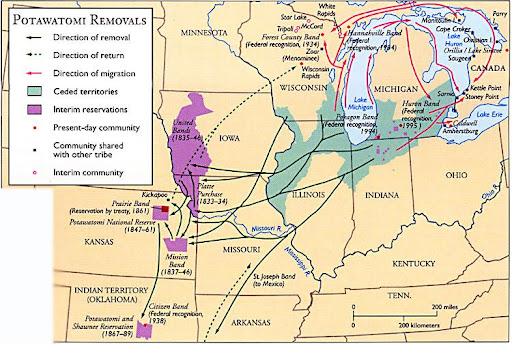

Figure 27. Map Demonstrating the Potawatomi Routes of Forced Removal, Migration to Avoid Removal, and Return from Removal. Reprinted from “Potawatomi Removals,” by Kalamazoo Public Library Staff (Ed.), 2020 (https://www.kpl.gov/local-history/kalamazoo-history/native-americans/match-e-be-nash-she-wish/). While many of the Potawatomi of northern Indiana were removed as part of the heartbreaking 1838 Trail of Death, the non-Pokagon Potawatomi of Southwest Michigan were given a two-year pardon due to Federal financial problems related to the economic depression of 1837 and were not removed until the summer of 1840 (Leatherbury, 1977, p. 67; Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 10 Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding…

Read More

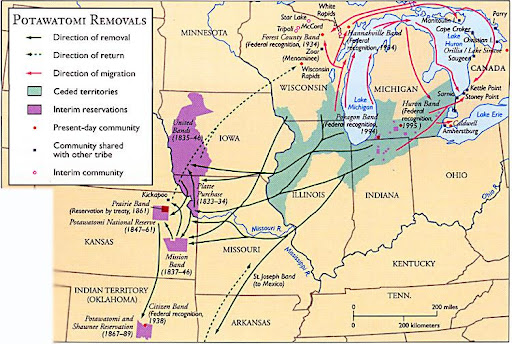

Figure 29. Map Demonstrating the Potawatomi Routes of Forced Removal, Migration to Avoid Removal, and Return from Removal. Reprinted from “Potawatomi Removals,” by Kalamazoo Public Library Staff (Ed.), 2020 (https://www.kpl.gov/local-history/kalamazoo-history/native-americans/match-e-be-nash-she-wish/). In the spring of 1841, a small group of the NHBP were displeased with their new reservation on the virtually treeless plains north of present-day Topeka, Kansas, and returned to Michigan with Lucius Buell Holcomb (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 12-13). According to Holcomb’s 1891 chronicle, during the winter of 1840-1841, members of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, whom the Army had removed, camped on the Osage River,…

Read More

Figure 30. 1858 Plat Map of Athens Township Showing the Pine Creek Reservation Outlined in Turquoise, Labeled as Maguago. Reprinted from “Map of Calhoun County, Michigan,” by Bechler & Wenig, & Herline & Hensel, 1858, (https://www.loc.gov/item/2012593023/). Upon returning to their former homeland after evading removal, NHBP members discovered they were not welcome at the former Nottawaseppi Reservation since it was flooded with settlers who desired the outstanding farmland. Fortunately, with the assistance of Lucius Buell Holcomb, as well as familiar and sympathetic settlers and clergy, available land in Section 20 of Athens Township was identified where the returning Tribal members…

Read More

Figure 32. Photograph of the Methodist Church on the Pine Creek Reservation as it Appeared ca. 1915. Reprinted from “Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress,” by J. Rodwan & V. Anewishki, 2009, p. 30. Annuity payments to the NHBP resumed in the mid to late 1840’s. It was in that same period that the Pine Creek settlement experienced the start of Methodist missionary activity. The subsequent founding of a church at Pine Creek would do much to shape the settlement for the next century. The goal of the Methodist missionaries was not to replace their religious…

Read More

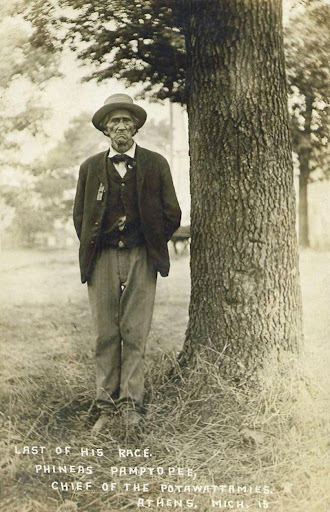

Figure 33. Photograph of Chief Phineas Pamptopee. Reprinted from “Last of His Race. Phineas Pamptopee, Chief of the Potawattamies,” by J. A. Little, 1915. In the summer of 1863, Chief John Moguago became ill. As he declined, he beckoned “Old” Pamptopee, his uncle, to his bedside and gave him a written transfer of power, along with other valuable Tribal papers. He then informed the President of the United States, as well as the Governor of Michigan, of the transfer (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 22). John (son of “Old” Moguago and grandson of Mogoagon) died on the reservation on May 3, 1863,…

Read More

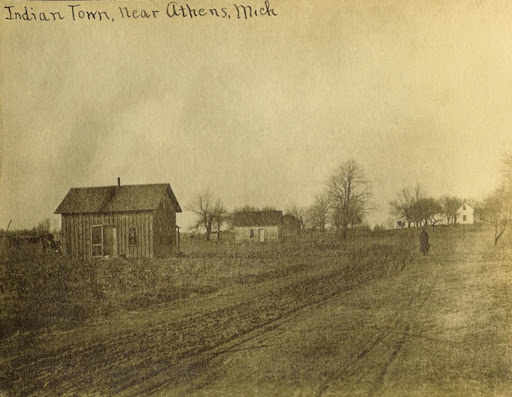

Figure 36. Photograph of the Pine Creek Reservation Along 1 ½ Mile Road, ca. 1910. Reprinted from “Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress,” by J. Rodwan & V. Anewishki, 2009, p. 30. In 1889, the $400 annual annuity the NHBP had been collecting since 1845, from the 1807 Treaty of Detroit, was compounded for a lump sum. The band received $20,000 in money (equivalent to $590,643 in 2021), distributed by Special Indian Agent George P. Litchfield of Salem, Oregon (Alioth Finance, 2021; Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p.…

Read More

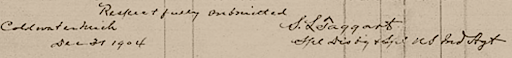

Figure 40. Scan of the Last Page of the Taggart Roll, Showing the Signature of Samuel L. Taggart, Special Indian Agent. Reprinted from “Taggart Roll,” by S. L. Taggart, 1904. During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, Phineas Pamptopee, the chief of the NHBP, was active in prosecuting claims activity, as regularly noted in the “Indiantown Inklings” newspaper articles (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 322). These claims involved lawsuits against the federal government for its failure in honoring financial obligations to tribes under various treaties, most of which involved…

Read More

Figure 42. Photograph of Chief Phineas Pamptopee’s Gravestone and Formal Headstone, by F. N. Ruffer, 2018a. Phineas Pamptopee, who had been chief for 50 years, died in 1914. The selected chief for the next ten years was his youngest son, Stephen Pamptopee. Steven became chief through designation by his father; he served for a ten-year period that ended in 1924. Steven was seldom photographed and was known for his retiring and mild disposition. He lived his entire life on the reservation and died suddenly of heart trouble in 1926 at 47 years old (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 23). Figure…

Read More

Figure 41. Group Posing at Athens Indian Mission Church, ca. 1915. Reprinted from “Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress,” by J. Rodwan & V. Anewishki, 2009, p. 24. Between 1904 and World War I, many families who had purchased land in the East Indiantown area sold the property. Most of the occupants lost their places on mortgages or sold them and moved back to the old reservation until Chief Phineas Pamptopee and his family were the only ones remaining (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 25; Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi,…

Read More

Figure 45. Photograph of Samuel Mandoka on the Banks of the St. Joseph River Near Mendon at the Site of an Old Indian Ford, Taken by Dr. C. J. Manby in 1924. Reprinted from “A History of Events Culminating in the Removal of the Nottawa-Sippe Band of Potawatomi Indians,” by J.W. Leatherbury, 1977, p. 128. The strong influential role of Samuel Mandoka within the Pine Creek settlement began during the lifetime of Steven Pamptopee. At Steven’s death in 1926, Samuel was not formally designated to the “office” as chief. However, he was essentially appointed by consensus of the residents of…

Read More

Figure 39. Photograph of NHBP Young Adults. Reprinted from “Pottawattamie Indians Having a Good Time,” by J. A. Little, 1909. In 1900, a federal census was taken in Athens Township (within Calhoun County, Michigan), numbering the people living at the Pine Creek settlement. This census included both the reservation and East Indiantown, placing the residents on special “Indian Population” census sheets, which differed from the rest of the township (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 194). [At the time], there were 21 households living in 20 dwellings, with a total population of…

Read More

Figure 49. Tribal Members Posing at a Home on the Pine Creek Reservation, ca. 1915. Those Pictured Are as Follows from Left to Right: Albert Mackety, Steven Pamp, Elizabeth Mackety, Mary Ann Pamptopee, Charlie Thomas Pamptopee, Agnes Pamptopee, and Guy Mandoka. Reprinted from “Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress,” by J. Rodwan & V. Anewishki, 2009, p. 24. Chief Samuel Mandoka died at the age of 71. He was succeeded not by a chief but by a committee. Albert Mackety and Levi Pamp provided the key political leadership of Pine Creek for the next 40 years…

Read More

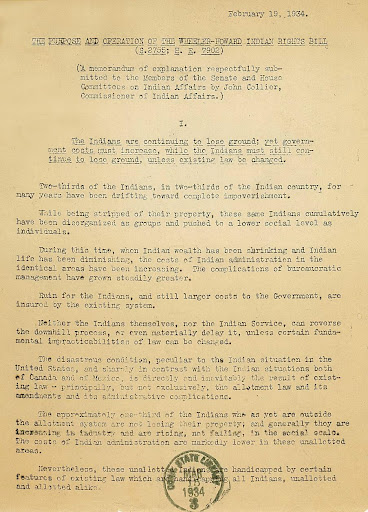

Figure 50. A Page from John Collier’s Memorandum to the Members of the Senate and House Committees on Indian Affairs. Reprinted from “The Purpose and Operation of the Wheeler-Howard Indian Rights Bill (S. 2755; H.R. 7902),” by J. Collier, 1934, p. 1 (https://cslib.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4005coll11/id/513/). Two-thirds of the Indians, in two-thirds of the Indian country, for many years have been drifting toward complete impoverishment. While being stripped of their property, these same Indians cumulatively have been disorganized as groups and pushed to a lower social level as individuals. During this time, when Indian wealth has been shrinking and Indian life has been…

Read More

Figure 51. Students posing at Beckett School in 1934. Bottom Row from Left to Right: Margaret Klein, Elma Mandoka, William Rogers, Agnes Pamp, and Leonard Pamp. Middle Row from Left to Right: William Miller, Christ Klein, Kenneth Miller, Balaam Pamp, David Mackety, June Rogers, Marjorie Moore, Marian Mandoka, Fern Pamp, and Mildred Pamp. Top Row from Left to Right: John Miller, Roy Miller, Vera Kissinger, Nellie Gray, Elizabeth Pamp, Hazel Mandoka, and Celia Pamp. Reprinted from “Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress,” by J. Rodwan & V. Anewishki, 2009, p. 28. The relative prosperity of the…

Read More

Figure 52. A Group of Tribal Youth on the Reservation, ca. Early 1950’s. From Left to Right: Roger Day, Richard Bush, Henry Bush, Amos Day, Jr, Gordon Bush, Dawn Bush, and Cecil Day. Reprinted from “Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress,” by J. Rodwan & V. Anewishki, 2009, p. 31. Some NHBP members joined the armed services during World War II, while others took jobs in urban industries. During these years, several men worked in factories in Battle Creek or Detroit; women also took industrial jobs (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron…

Read More

Figure 54. Photograph of a Gathering of NHBP Tribal Members, ca. 1950’s or 1960’s. Reprinted from NHBP Historical Collection, (n.d.). After World War II, the pattern of work off the reservation continued to grow. For many of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, this period marked the first participation in the urban labor market (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 353). By the end of the war, factory employment and other urban jobs had largely replaced the earlier dependence on seasonal farm work and subsistence farming. In the 1950s, the economic…

Read More

Figure 55. Photograph of the Pine Creek Reservation, Pre-Reaffirmation. Reprinted from NHBP Historical Collection, 1961. By 1960, most of the group’s members were no longer living at Pine Creek but had moved to cities in southern Michigan that provided employment opportunities. Continuing a trend to seek off-reservation employment that had begun in the 1940s, more and more of the young adults moved out of the core geographical area centered at Pine Creek. The dispersal resulted from a rapidly increasing birth rate which caused significant population pressure on the limited Pine Creek land. The HPI population had 30 known births from…

Read More

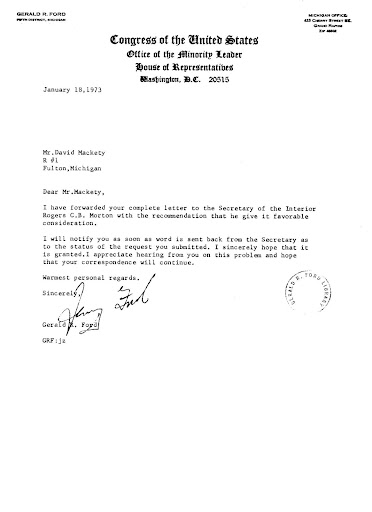

Figure 58. Gerald R. Ford to David Mackety, 1973, January 18 [Letter]. Gerald R. Ford Library. In the spring of 1972, the NHBP decided to make their first concerted effort since 1934 at seeking federal reaffirmation. This effort continued for several years with little progress despite considerable effort. On March 11, 1972, Tribal Council adopted a resolution to …inform the Minneapolis Area Office, Bureau of Indian Affairs Land Operation, of its decision to apply for federal status as an Indian reservation and to ask the State of Michigan to have the Pine Creek Reservation transferred to the Federal government as…

Read More

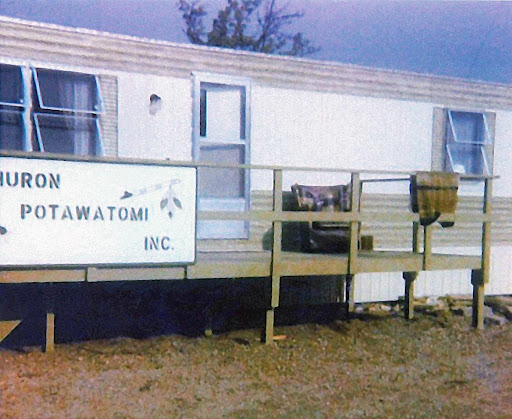

Figure 57. Huron Potawatomi Inc. Administration Building, ca. 1976. Reprinted from “Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress,” by J. Rodwan & V. Anewishki, 2009, p. 31. The decade of the 1970s proved to be a pivotal period in the development of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi’s political organization. Since the late 1960s, David Mackety had met with members urging the group to establish a formal structure to apply for funds, elicit additional member involvement, and gain outside organizational support. By 1970, the band leaders felt no time could be lost if the group was…

Read More

Between 1980 and 1986, one major focus of HPI’s efforts was the preparation of the Federal acknowledgment petition for consideration under a new administrative process established under regulations adopted by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Those regulations required tribes, whose government-to-government relations with the United States had been improperly terminated to submit documentation that confirmed that their tribe had continued to exist as a distinct government from treaty times to the present. A partial, documented petition, focusing on the historical record, was submitted to the Branch of Acknowledgment and Research (BAR) at the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) on January…

Read More

Figure 64. Photograph of the Pine Creek Reservation from the Pow Wow Grounds Looking Towards the Government Center, by J. Rodwan. The NHBP has accomplished a great deal since federal reaffirmation in 1995. The Pine Creek Reservation has become a secure homeland quickly developing into a first-class Tribal community with a beautiful Government Center, Department of Public Works, Community & Health Center, energy-efficient homes, and Justice Center. Education, health, housing, and environmental programs continually strive to improve the Tribe’s quality of life. Despite these recent developments, the Reservation still retains its rural flavor, with unspoiled forests, fields, and Pine Creek…

Read More

Figure 61. Signing of the 1995 Federal Reaffirmation Document in the White House Treaty Room. From Left to Right: Dale Kildee (U.S. Congressman for Michigan’s 9th Congressional District in 1995), Irene Wesley (Tribal Elder), Shirley English (NHBP Tribal Council Chairwoman in 1995), Ada E. Deer (Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Indian Affairs), Michael J. Anderson (Deputy Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs), and Loretta Avent (President Bill Clinton’s Special Assistant for Intergovernmental Affairs). Reprinted from NHBP Historical Collection, December 19, 1995. The Huron Potawatomi’s first response to the Obvious Deficiency Review Response letter (OD) sent in the fall of 1987, was submitted…

Read More

Figure 69. FireKeepers Casino and Hotel, by JCJ Architecture, ca. 2021. 2008 NHBP secures bond financing for the development of FireKeepers Casino. NHBP’s FireKeepers Casino offering is the only casino project – tribal or commercial – to receive funding before the financial collapse. 2009 After more than ten years of planning, strategy, and vision, the NHBP opened the doors to FireKeepers Casino on August 5, 2009. FireKeepers features a 111,700-square foot gaming floor with 2,900 slot machines, 70 table games, multiple restaurants and lounges, a live poker room, and a bingo room. This $300 million project created a unique…

Read More

Figure 70. Photograph of the Waséyabek Development Company Headquarters in Downtown Grand Rapids, by F. N. Ruffer, 2018. Waséyabek Development Company, LLC (WDC) is a 100% Tribally-owned holding company that manages the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi’s non-gaming economic development activities. By fostering the development of a stable, diversified economy for members of the Band, WDC seeks to contribute to the Tribe’s long-term sustainability and economic self-sufficiency by providing revenue and diverse employment opportunities for Tribal Members. The need to diversify Tribal economies is well established, as are successful strategies. Nation-building and Tribal community expansion are supported by revenue…

Read More