In the 1700s, three groups of Potawatomi were identified based primarily on their locations (Sultzman, 1998, p. 3):

- The “Detroit Potawatomi” of southeast Michigan

- The “Prairie Potawatomi” of northern Illinois

- The “Saint Joseph Potawatomi” of southwest Michigan

The Beaver Wars officially ended on August 4th, 1701, with the signing of a treaty known as the “Great Peace of Montreal.” The governor of New France was present, as were 1,300 representatives from 39 Native American Tribes, including the Iroquois, who also relinquished their previously conquered territory (Francis et al., 2006).

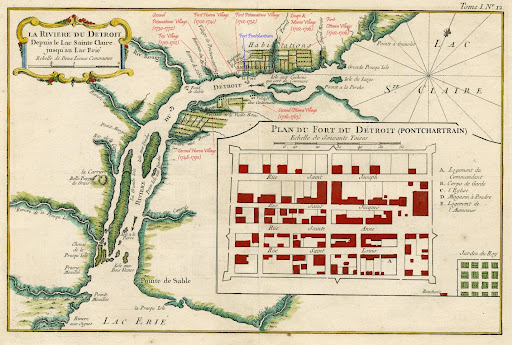

Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac landed on July 24th, 1701, and began preparing to construct Fort Pontchartrain at Detroit after the signing of the treaty on August 4th (Sewick 2016). This fort was founded primarily for military and economic reasons; however, according to Cadillac’s Papers in a report written September 25th, 1702, he referenced a more overarching Utopian goal, which was to “bring the tribes together” (Authority, 1901). Cadillac compelled every tribe he could to join the settlement around Fort Ponchartrain; however, the results did not always align with his vision (Sewick, 2016). There was a notable amount of fighting between several tribes, primarily the Fox, Kickapoo, “Loup” (most likely the Oppenago), Mascouten, Ottawa, and Wyandot (Huron) (Sewick, 2016).

The Potawatomi kept their distance from the Fort the first decade of its existence to allow the intertribal fighting to subside, eventually arriving at Fort Pontchartrain between 1712-1714 (Sewick, 2016). The Potawatomi lived in temporary settlements between the Wyandot (Huron) and French forts until safety and stability increased around the fort; at that point (around 1732), they moved downstream and established a permanent establishment on the site of the old Fox village, which is near the current Ambassador Bridge site (Sewick, 2016).

During the summer months at Fort Ponchartrain, tribes raised various crops and traded with the French; however, during the winter, most, if not all, of the villages would empty, and each tribe would leave the Fort to hunt and camp in the forests of Michigan and Ohio (Sewick, 2016).

While Detroit’s French population expanded to 270 within the first ten years, the Native American people outnumbered the French more than four times (Sewick, 2016)! There were 580 Native American warriors in Detroit by 1736, which, if one includes women and children, suggests a total population of approximately 2,000 (Sewick, 2016). Interestingly, Detroit’s entire Caucasian population was only 800 as late as the mid-1760s (Sewick, 2016).

References:

Authority. (1901). Historical Collections: Collections and Researches Made by the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society: Vol. XXIX. Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co.

Bellin, J. N. (1764). La Riviere Du Detroit Depuis le Lac Sainte Claire jusqu’au Lac Erie (Detroit Historical Society) [Map]. Jacques Nicholas Bellin; Detroit Historical Society.

Francis, D., Germain, J., and Scully, A. (2006). Voices and Visions. Oxford University Press.

Potawatomi. (2019). In New World Encyclopedia. New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Potawatomi&oldid=1015500

Sewick, P. (2016). Detroit Urbanism: Indian Villages, Reservations, and Removal. Detroit Urbanism. Retrieved from http://detroiturbanism.blogspot.com/2016/03/indian-villages-reservations-and-removal.html

Sultzman, L. (1998). Potawatomi History. Retrieved from http://www.tolatsga.org/pota.html

Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc. (1995). United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs Branch of Acknowledgement and Research. Retrieved from https://www.bia.gov/sites/bia.gov/files/assets/as-ia/ofa/petition/009_hurpot_MI/009_pf.pdf