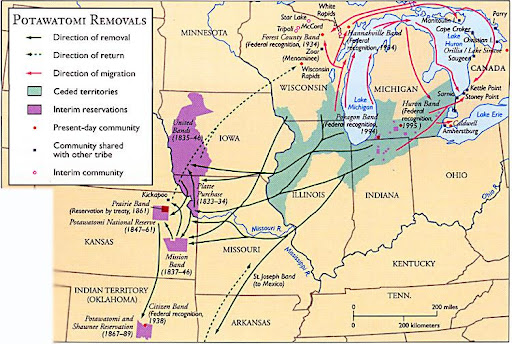

Figure 29. Map Demonstrating the Potawatomi Routes of Forced Removal, Migration to Avoid Removal, and Return from Removal. Reprinted from “Potawatomi Removals,” by Kalamazoo Public Library Staff (Ed.), 2020 (https://www.kpl.gov/local-history/kalamazoo-history/native-americans/match-e-be-nash-she-wish/).

In the spring of 1841, a small group of the NHBP were displeased with their new reservation on the virtually treeless plains north of present-day Topeka, Kansas, and returned to Michigan with Lucius Buell Holcomb (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 12-13). According to Holcomb’s 1891 chronicle, during the winter of 1840-1841, members of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, whom the Army had removed, camped on the Osage River, about 100 miles from Independence, Missouri. Holcomb stayed with the band for nearly three months until payment of approximately $20 per person (equivalent to $662.67 in 2021) was made. Holcomb and 11 members of the band employed a team and returned to Independence, Missouri, where they stayed the remainder of the winter. Among the defectors were Chief John Moguago’s sister and her four children (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 279).

In the spring, they returned to the Nottawasippe Prairie where Holcomb wrote in his unique style, they “…came to the Town of Athens Evry [sic, “every”] one Glad to see the Indians once more. It has been so lonesome they we [sic] would have stay. Some thought it was wiced [sic, “wicked”] to take them of [sic, “off”] away among wild Indians whar [sic, “where”] they would be so Lonesome and on the open Prarie they cant [sic, “can’t”] make Sugar to Eat (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 279).

Soon after that, Chief Moguago, who had a long, lonely winter with plenty to eat, but only three people to share it with, was located. The returning group chose a location to cultivate crops; the same place, said Holcomb in his 1891 memoir, on which they now owned and lived (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 280).

By 1842, they had settled near Dry Prairie in Calhoun County, Michigan, within the former Nottawaseppi Reserve. That same year, they resumed contact with Michigan’s Federal Indian Agent (Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc., 1995, p. 9).

Ultimately, the number of NHBP members that escaped, hid undetected, and returned is unknown definitively, but 40 is realistic (Rodwan & Anewishki, 2009, p. 13).

References:

Alioth Finance. (2021). $20 in 1842 → 2021. Inflation Calculator. https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1842?amount=20

Kalamazoo Public Library Staff (Ed.). (2020). Potawatomi Removals [Map]. https://www.kpl.gov/local-history/kalamazoo-history/native-americans/match-e-be-nash-she-wish/

Rodwan, J., & Anewishki, V. (2009). Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi: A People in Progress. Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi Environmental Department.

Summary Under the Criteria and Evidence for Proposed Finding Huron Potawatomi, Inc. (1995). United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs Branch of Acknowledgement and Research. https://www.bia.gov/sites/bia.gov/files/assets/as-ia/ofa/petition/009_hurpot_MI/009_pf.pdf