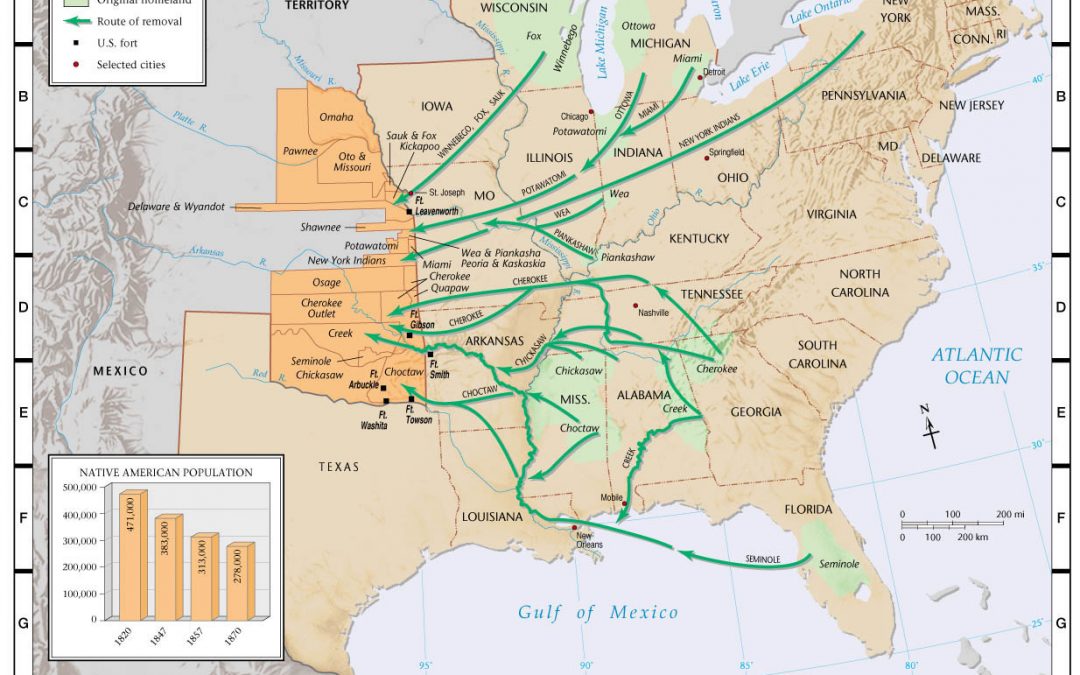

Figure 24. Results of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Reprinted from “Native American Land Cessions, 1829-1850,” by Pearson Education, 2003 (https://wps.pearsoncustom.com/wps/media/objects/5407/5537171/atlas/Resources/ah3_m002.jpg).

While the Huron Potawatomi, and other Potawatomi, generally maintained peaceful relations with their new non-Indian neighbors, the increased pressure from settlers, many of whom illegally entered Indian lands, often resulted in violent conflict between settlers and the resident Indian tribes. The solution championed by Andrew Jackson and others in the U.S. Government became the nineteenth-century policy referred to as “Indian Removal,” by which Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River would be encouraged to sign treaties giving up the remainder of their lands and be relocated to lands west of the Mississippi.

The Indian Removal Act, signed May 28th, 1830, further empowered the U.S. Government to strip the Native Americans of their land rights. This Act created a process and funds where the President could conduct land-exchange (“removal”) treaties, granting land west of the Mississippi River (to be called “Indian Territory”) to tribes that agreed to give up their homelands.

The Indian Removal Act did not legally order the involuntary removal of any Native Americans; however, the Act allowed the Jackson administration to freely “persuade, bribe, and threaten” tribal leaders to sign removal treaties (Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830, n.d., p. 2). The new Act granted the Indians financial and material assistance to relocate to a new homeland and restart their lives while promising the tribes would live under the U.S. Government’s protection (Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830, n.d., p. 2).

Sadly, a shifty, underhanded method usurped the previously established approach and involved forcing tribes into smaller areas where their only real income was annuities. Then, government traders (the only people legally allowed to trade with Native Americans) would extend credit. As their debts compounded, the tribes were forced to sell their land to pay their liabilities.

As a result of the pressure to sign these treaties, sharp divisions within Native American nations arose because various tribal leaders promoted different responses to the ambiguity surrounding removal (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 2). All too frequently, U.S. Government officials disregarded tribal leaders who resisted signing removal treaties and worked with those who favored removal (“Potawatomi,” 2019, p. 2).

Jackson’s plan succeeded. By the end of his two terms, he had signed into law nearly seventy removal treaties resulting in the relocation of approximately 50,000 eastern Native Americans to the new Indian Territory located west of the Mississippi River (Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830, n.d., p. 2). Consequently, millions of acres of fertile land east of the Mississippi were now open to white settlers.

References:

Indian Treaties and the Removal Act of 1830. (n.d.). Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute. Retrieved from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1830-1860/indian-treaties

Pearson. (2003). Native American Land Cessions, 1829-1850 [Map]. Pearson Education. https://wps.pearsoncustom.com/wps/media/objects/5407/5537171/atlas/atl_ah3_m002.html

Potawatomi. (2019). In New World Encyclopedia. New World Encyclopedia. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Potawatomi&oldid=1015500

Transcript of President Andrew Jackson’s Message to Congress “On Indian Removal” (1830). (1830). ourdocuments.gov. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=25&page=transcript